Contact: Joseph Frye-Jones and/or Alan Marshall

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Researchers at the National MagLab are taking a fresh look at a space rock that plummeted to earth more than 50 years ago and getting a clearer picture of its complex makeup.

Powerful spectrometry found only at the MagLab is helping to identify the vast array of compounds inside the meteorite, providing clues about the universe before our solar system existed.

“This can shed light on how complex organic material, such as the amino acids needed for life, is out in space,” said FSU graduate research assistant Joseph Frye-Jones, who works in the MagLab’s Ion Cyclotron Resonance facility under Professor Alan Marshall, the chief scientist for ICR.

A sample from the Murchison meteorite, which fell in Victoria, Australia in 1969.

Image credit: Joseph Frye-Jones

To conduct the research, Frye-Jones obtained a fragment of the Murchison meteorite, a billions of year old rock which fell in Australia in 1969. Much of the previous analysis of the Murchison happened soon after its discovery using state-of-the-art equipment at the time. But the past five decades has offered exciting improvements in both the techniques and instrumentation, helping Frye-Jones get a much more detailed look to sort through the myriad molecules inside.

“The technique that we are using… has been steadily getting better and better as technology improves. With the highest resolution mass spectrometer in the world, we can look at things that others cannot,” Frye-Jones said.

Pieces of the Murchison meteorite examined at the National MagLab

Image credit: Joseph Frye-Jones

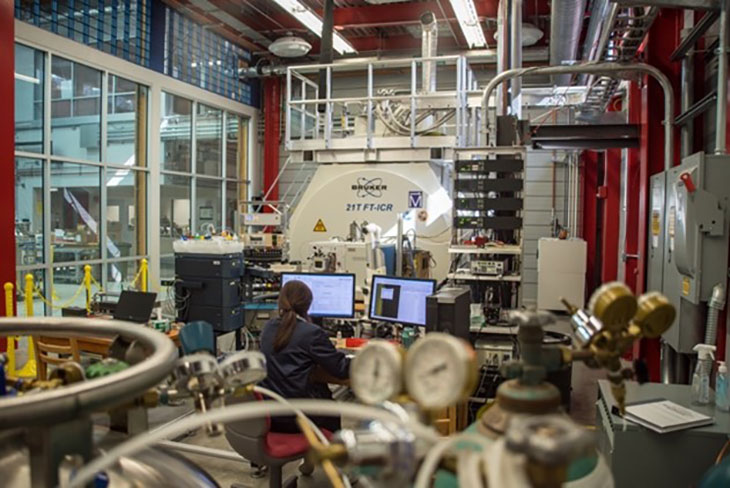

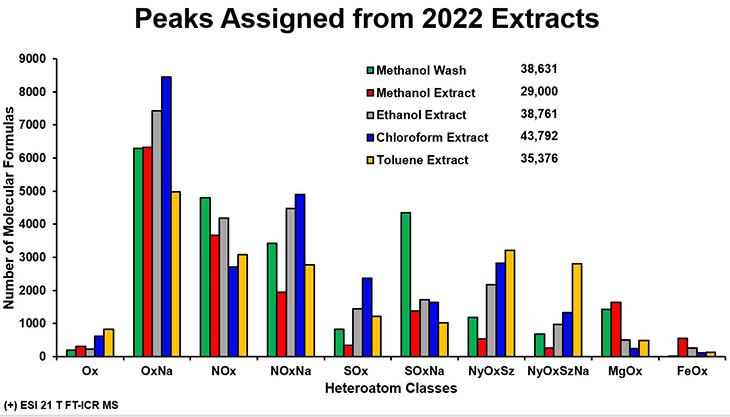

Researchers used a mortar and pestle to crush up the meteorite sample, then dissolved the pieces in organic solvents, such as methanol and ethanol, before examination using the MagLab’s record 21-tesla FT-ICR spectrometer, the highest performing system in the world for ion cyclotron resonance. This instrument provides researchers the ability to identify the chemical makeup of complex mixtures with high resolution and mass accuracy and has been instrumental in analyzing petroleum, PFAS and dissolved organic matter samples.

The 21-Tesla Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance mass spectrometer at the National MagLab.

The analysis found tens of thousands of molecular signatures in a small sample of the meteorite. Each of those has the potential to represent several unique molecules, meaning the meteorite is far more chemically complex than anticipated, likely among the most complex materials ever known.

“The Murchison meteorite is at least 5.5 billion years old, one billion years older than Earth, and this is just as complex as petroleum deposits, which are some of the most complex mixtures that we have analyzed in our lab. These findings are showing just how complex the organic materials in space can be,” said Frye-Jones.

“It is giving us a glimpse at the origins of our planet and solar system,” he said.

Now, Frye-Jones is keeping his eyes on outer space for another project. His lab has obtained two lunar samples from NASA’s Apollo 12 and 14 missions.

“We are going to take the lessons learned from the meteorites and move into lunar soil to examine its complexity,” said Frye-Jones.

The work is featured at the American Chemical Society's Spring 2023 meeting.

- Read more from the American Chemical Society here: Two meteorites are providing a detailed look into outer space

- View an interview with Frye-Jones here: Two meteorites are providing a detailed look into outer space

Story by Edan Schultz