Contact: Zachary Boehm

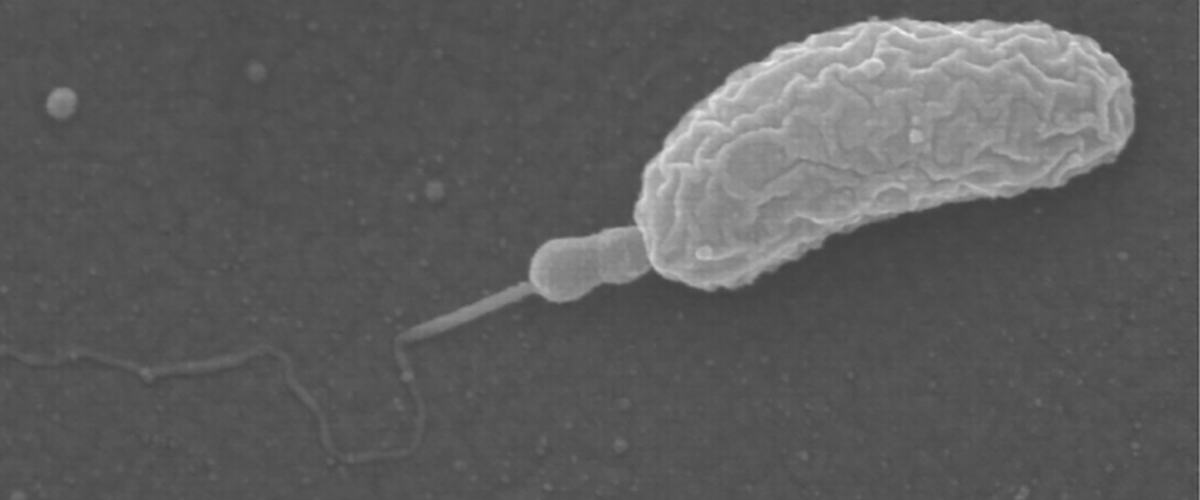

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Roughly 430 million years ago, during the Earth's Silurian Period, global oceans were experiencing changes that would seem eerily familiar today. Melting polar ice sheets meant sea levels were steadily rising, and ocean oxygen was falling fast around the world.

At around the same time, a global die-off, known among scientists as the Ireviken extinction event, devastated scores of ancient species. Eighty percent of conodonts, which resembled small eels, were wiped out, along with half of all trilobites, which scuttled along the seafloor like their distant, modern-day relative the horseshoe crab.

Now, for the first time, a team of researchers from Florida State University and the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory (National MagLab) has uncovered conclusive evidence linking the period's sea level rise and ocean oxygen depletion to the widespread decimation of marine species. Their work highlights a dramatic story about the urgent threat posed by reduced oxygen conditions to the rich tapestry of ocean life.

Former FSU graduate student Andrew Kleinberg, a co-author on the paper, collects samples from Silurian limestones in Tennessee.

The findings from their study were published in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

Although other researchers had produced reams of data on the Ireviken event, none had been able to definitively establish a link between the mass extinction and the chemical and climatic changes in the ocean.

"The connection between these changes in the carbon cycle and the marine extinction event had always been a mystery," said lead author Seth Young, an assistant professor in FSU's Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science and a researcher in the MagLab Geochemistry Group.

To address this old and obstinate question, Young and his co-authors deployed new and innovative strategies. They developed an advanced multiproxy experimental approach using stable carbon isotopes, stable sulfur isotopes and iodine geochemical signatures to produce detailed, first-of-their-kind measurements for local and global marine oxygen fluctuation during the Ireviken event.

"Those are three separate, independent geochemical proxies, but when you combine them together you have a very powerful data set to unravel phenomena from local to global scales," Young said. "That's the utility and uniqueness of combining these proxies."

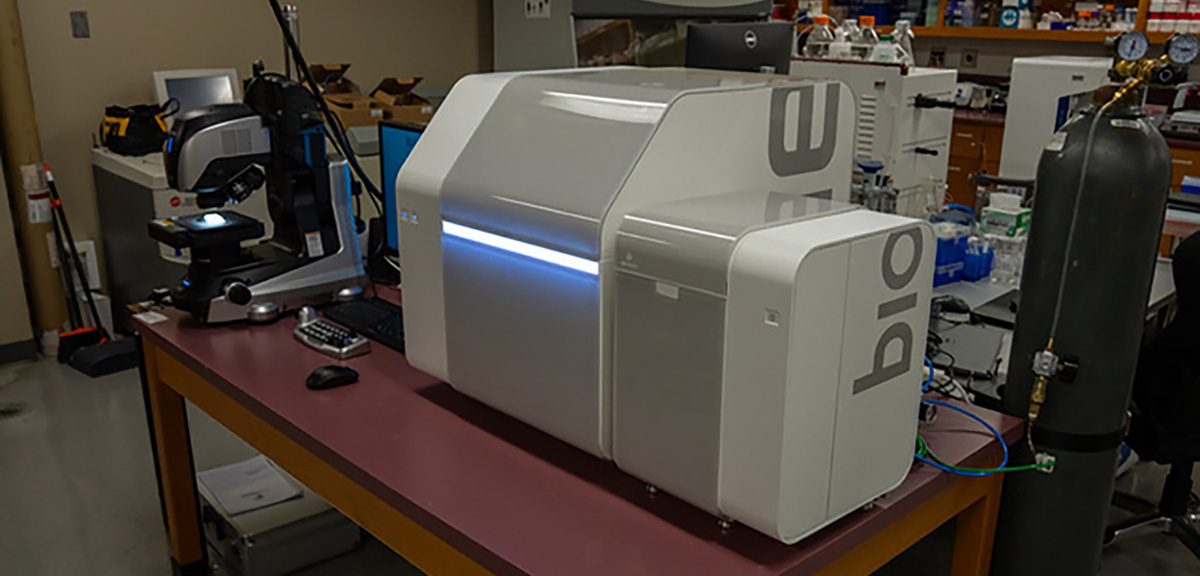

Young and his team applied their approach to samples from two geologically important field sites in Nevada and Tennessee, both of which were submerged under ancient oceans during the time of the extinction event. After analyzing their samples at the National MagLab, the connections between changes in ocean oxygen levels and mass extinction of marine organisms became clear.

The experiments revealed significant global oxygen depletion contemporaneous with the Ireviken event. Compounded with the rising sea level, which brought deoxygenated waters into shallower and more habitable areas, the reduced oxygen conditions were more than enough to play a central role in the mass extinction. This was the first direct evidence of a credible link between expansive oxygen loss and the Ireviken mass extinction.