Contact: Rob Spencer

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Thousand-year-old tropical soil unearthed by accelerating deforestation and agriculture land use could be unleashing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, according to a new study from researchers at Florida State University.

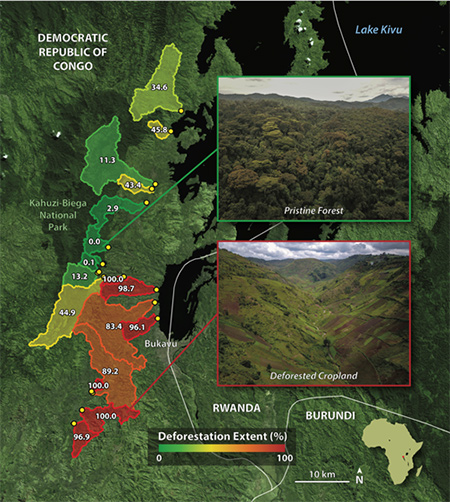

In an investigation of 19 sites in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, researchers discovered that heavily deforested areas leach organic carbon that is significantly older and more biodegradable than the organic carbon leached from densely forested regions.

Released from deeper soil horizons and leached by rain into waterways, that older, chemically unstable organic carbon is eventually consumed by stream-dwelling microbes, which devour the rich compounds and respire carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere. It's a process that could jeopardize local ecosystems and further fuel the greenhouse effect, researchers said.

Vast tracts of once-pristine land in the Democratic Republic of the Congo have been denuded of their forests. As the country's population continues to balloon, more area is needed for agriculture land use.

"In many ways, this is similar to what happened in the Mississippi River Basin 100 years ago, and in the Amazon more recently," said study author Rob Spencer, an associate professor in FSU's Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science who is affiliated with the National MagLab's Geochemistry Group. "The Congo is now facing conversion of pristine lands for agriculture. We want to know what that could mean for the carbon cycle."

While the broader effects of deforestation on the carbon cycle are well known, researchers said their findings, published today in the journal Nature Geoscience, suggest there is an additional pathway or leakage of carbon into rivers from soil churned by deforestation and land conversion.

Travis Drake, former FSU postdoc and current researcher at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zürich, sampling streams in the Congo.

"At this point, it's hard to know the magnitude of this flux and thus the relative importance of this process compared to other anthropogenic sources of CO2, but it is likely to grow with additional deforestation and land-use conversion," said former FSU postdoctoral researcher Travis Drake, the study's lead author. "We hope this paper stimulates more research into the relative importance of this process."

To better distinguish the different soils in their study, researchers analyzed the dissolved organic carbon drained from study sites into outflowing streams and rivers. Using ultrahigh-resolution mass spectrometry data generated by cutting-edge tools at the FSU-headquartered National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, the team found that the older dissolved organics discharged from deforested areas were more energy-rich and chemically diverse than those from better-preserved forests

Overall, forested areas released significantly more dissolved organic carbon than deforested areas. But the dissolved organics that did emanate from the deforested and land-converted regions were exceptionally biolabile, or suited for microbial consumption.