Break out the silly ties, pretty bouquets and photo-plastered coffee mugs: It's the time of year when we honor moms and dads.

At the MagLab, we salute parents everywhere by taking a look at a few of our in-house parent-scientists. We wondered: Do scientists and engineers parent differently than other moms and dads? What's it like being raised by a scientist? And what can the rest of us learn from the way people in the STEM fields (science, technology, engineering and math) bring up their kids?

Parent like a scientist

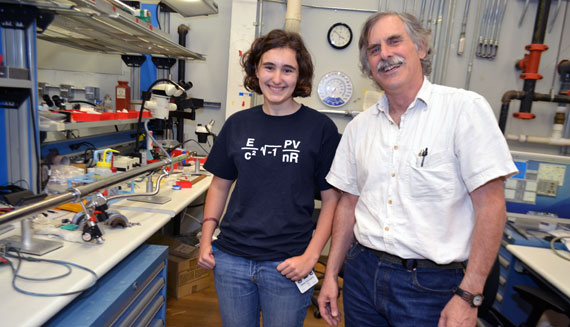

We tracked down physicist Scott Hannahs, dad to two teenagers, and asked him point blank: "Do scientists make better parents?"

Maia with dad and MagLab physicist Scott Hannahs.

Brow furrowed, Hannahs reflected a moment, illustrating his scientific approach to everything, kids included. Then, not having done or read a study on the subject, he gave a qualified: "Probably."

"Because in science you tend to have to justify everything, and we do try to justify everything to our kids," explained Hannahs, whose wife is a biologist. "It helps us be consistent, I think, so the rules don't change from day to day, because they're based on first principles type things."

The couple's scientific training, Hannahs said, molded them into parents who stress logic over emotions and facile because-I-said-so's.

"Usually we give them reasons when they ask for things," said Hannahs, who, despite the bumper sticker on his Miata ("Embarrassing my kids is a full-time occupation" – a gift from younger daughter Clea) passes most days directing the MagLab's Scientific Instrumentation & Operations Division. "That pushed them to deal more logically and develop reasoning. If they can come up with good reasons why we're wrong, we'll listen, too."

The reign of rationality holds firm in the Hannahs household, confirmed elder daughter Maia, 17. Her parents never, for example, introduced the concept of Santa. When first learning about St. Nick from classmates, Maia's first thought was, "Does he have to travel at light speed to deliver all those presents?"

"Our family, we're complete hyper-rationalists," said Maia, who will be a high school senior in the fall. "How we approach anything is almost always from the science point of view."

MagLab chemist Amy McKenna keeps her scientist hat on when she comes home to her three elementary-age children in the evening. "The joke is, ‘Mommy's an experimentalist,'" said McKenna. "'We rely on data. Let's see what happens and examine the data and determine if our hypothesis was correct.' "

MagLab chemist Amy McKenna and children in their garden.

McKenna lets her kids experiment with everyday decisions. What will happen if I leave my jacket at home on a cold day? If I don't bring lunch money to school? If I jump on that tree?

"In the back of my head is always teaching them how to be experimentalists," said McKenna. As user program manager of the lab's Ion Cyclotron Resonance Facility, she admits to coddling visiting scientists more than her own issue. "I'm a big believer in letting them make poor choices, and let consequences teach the lessons when they're younger and the stakes are low."

Teaching kids to be rational and good experimenters are two ways to mold young scientists. MagLab physicist Bill Brey has practiced a similar approach with his sons: Teach them to solve problems.

MagLab physicst Bill Brey, center, with sons Jasper (left) and Max (holding Kepler the cat).

Max, at 17 Brey's younger son, has been fishing with his dad since he was about 11. Although his father knows a thing or two about angling, he never taught those tricks to Max. Rather, he "facilitated," as Max put it, encouraging the boy to research the topic, ask bait shop owners for advice and decide for himself where to drop the lines.

Max, a lanky, voluble red-head, expounded: "I think most people, when they learn to fish, learn from their dads. Like, their dads know all about it, and their dads have been going fishing with their friends. And sometimes, when you're old enough, you're allowed to come fishing with your dad and his friends. And they tell you absolutely what to do and they hold your hand, literally, while you cast, and do everything for you, until you are too embarrassed to allow them to do it anymore. And then you do it yourself. And then you are the dad and you do that to your son.

Jasper Brey (on guitar) and brother Max (on dobro) have done well in the sciences, but remain passionate musicians.

"But that," continued Max, "is not how my dad did it at all." And that, he said, is why he turned into such a good fisherman.

Seeing science everywhere

All the MagLab parents we spoke with agreed: It isn't hard to bring science into kids' lives: Science is everywhere. Parents just need to point it out.

Yan Xin, a materials scientist in the MagLab's Magnet Science and Technology division, travels often for work and holidays with physicist husband Jun Lu, also at the MagLab, and their 10-year-old daughter, Annette. Those adventures, Xin said, are great opportunities for teaching science. After collecting rocks on a Greek beach, for example, they put them in water to see what would happen. Annette was so excited that some rocks floated, said Xin, that she later brought some into school, sharing tales of her hands-on lesson in density.

Annette Lu, center, with dad Jun Lu and mom Yan Xin, both MagLab scientists, at the Chihuly Garden and Glass museum in Seattle.

In the Brey family, dad invites his sons to help fix things around the house. The DIY efforts are not just a chance to learn how stuff works, said Max; they also train his brain for science and other challenges.

"Intellectually, if you go through the process of figuring out how to solve that problem, then, when there's another one, you can do that," Max said.

At their dinner table, the Hannahs clan often debates politics and current events; conversations that can quickly seguey into science. Hannahs and his wife point out to their girls how science can be used, misused and misconstrued by different people, and that it pays to be scientifically literate.

Over at the McKennas, the garden is an ongoing family science project where new plants and techniques are constantly tested. Trips to the beach translate into lessons in marine biology, and the ride there is a chance for mom to test her offspring's powers of observation with car games.

"They're doing science all the time," said McKenna. "They just don't realize it."

Feed the curiosity

If Roxanne Hughes, director of the MagLab's educational outreach programs, could give parents just one piece of advice on raising scientists, it would be this: Let them be kids.

"Most children are naturally curious," said Hughes, whose programs and resources reach thousands of children every year. "And I think that as long as you as a parent continue to support that curiosity, you're helping them be scientists."

By Kristen Coyne