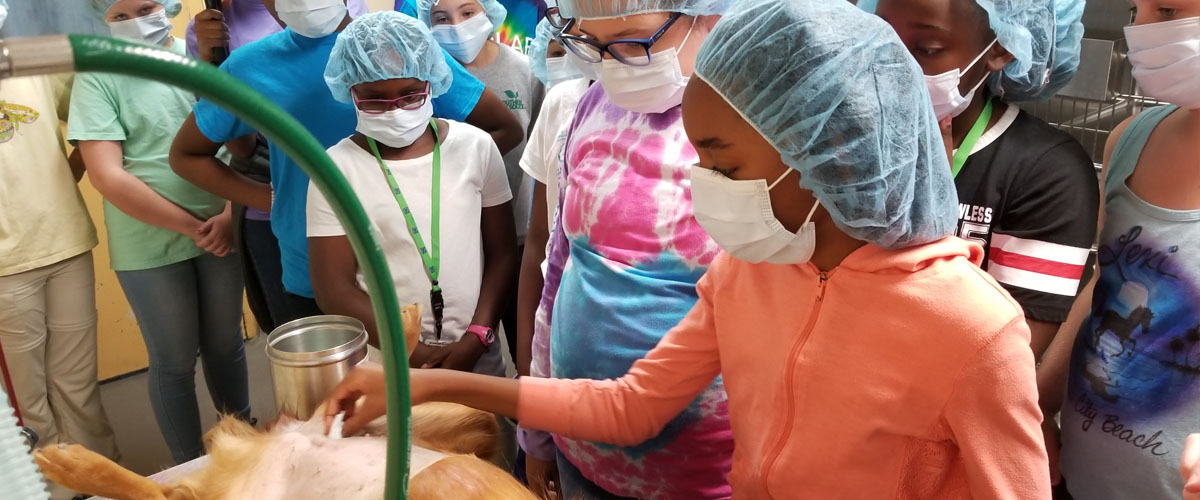

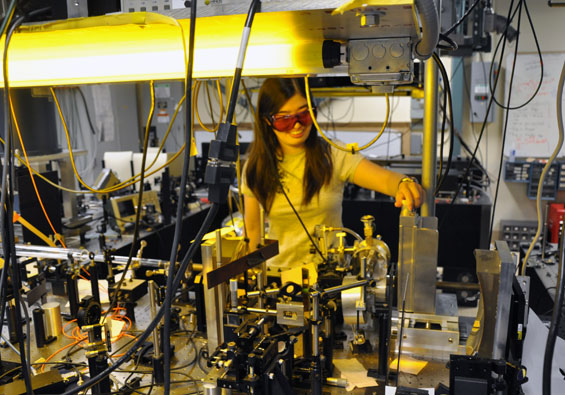

Luyi Yang, a postdoc at the MagLab's Pulsed Field Facility, hears that "work smarter" refrain from her mentor, Scott Crooker. "He always says to me that I'm a postdoc, not a graduate student anymore," she said. "My postdoc appointment is only a couple of years, so I need to be very productive … If there was something that didn't work, I shouldn't spend a month to figure out what's wrong, I should switch to some new topic."

Postdoc Luyi Yang works on an optics experiment.

Time is of the essence, agreed MagLab physicist Theo Siegrist, Besara's supervisor. That makes the mentor-postdoc relationship all the more critical. "To show productivity, the postdoc needs to publish within less than 12 months, so that new results can be presented when interviewing for jobs," Siegrist said. "If the relationship is fine, then the postdoc can be productive and build a career. If the relationship does not work, then it very often affects the career of the postdoc negatively."

As months pass, postdocs typically come to treat their mentors – and be treated by them – more as peers. That shift from underling to colleague can be tricky, said MagLab postdoc liaison Roberts, especially for postdocs used to treating their professors deferentially. Clear communication is key: "If you really want to learn about x, y and z, ask for it," she said.

Postdocs should gradually claim more control over their work, agreed Tozer. But that process can be trying, and he and postdoc Grockowiak regularly lock horns. Their tug-of-war is symbolized by two eggcups – one shaped like a goat, the other a ram – staring each other down on a shelf in his office. Said Tozer, "I have met my match."

Navigating the wide world of science

Postdocs don't have to head to their supervisor's office for advice. As they mature into independent scientists, they should build a broad support network. No single mentor can meet their every need.

Julia Wildeboer.

Ernesto Bosque, an engineering postdoc with the MagLab's Applied Superconductivity Center, is part of a team building a new kind of superconducting magnet dubbed the Platypus. His role: simulate experiments using complex software before the team actually runs them. When Bosque updates the team on his work during their regular meetings, he can count on an earful.

"Everyone has free reign to just go ahead and start throwing darts – ‘Well did you consider this?' … ‘Did you look at this?' … ‘How about this?'" said Bosque. He sees every question as a chance to be better. "As an engineer, you have to be able to accept constructive criticism, quickly recognize mistakes, and figure out how to ultimately get it right."

Postdoc Ernesto Bosque with a test magnet.

Sometimes finding relevant feedback means hopping a plane to meet specialists at conferences. "This traveling issue is crucial for postdocs," said Wildeboer.

Postdoc Yang agrees. "I go to conferences once every few months so that I can exchange ideas with other postdocs or students or experts in the field, if I have any questions," she said. "And also I can meet new people who can send me samples to study."

The soft skills of hard science

Scientists need to be savvy networkers. But that art, like many of the "soft skills" that help people build careers, is not always explicitly taught. To succeed, postdocs need to learn skills such as marketing, job-hunting, getting along with people from different cultures, time management and communicating their esoteric research to a broader audience.

MagLab postdoc liaison Roberts offers workshops and other resources on these skills and helps postdocs and their mentors with a tool designed to make sure they stick: the IDP. That stands for "independent development plan." The NSF requires that grant applications include IDPs for postdocs who would be employed under the grants; the National Institutes of Health also encourages the use of IDPs. Whether required or not, Roberts encourages all MagLab postdocs and their mentors to develop IDPs, and the practice has been catching on. "It forces you to think about things you wouldn't otherwise think about," said Roberts.

Roberts urges the lab's junior scientists to get as serious about managing their careers as they are about managing their science. The first day of your postdoc, she tells them, should be the first day of your job search.

Two years into her postdoc, Grockowiak takes that advice to heart. With the support of her mentor, who introduces her to potential employers, she is exploring her next professional step. Busy writing up her research for publication, she can now look back on her first stressful months at the lab with some perspective.

"The upside of that is that it makes me extremely independent," she said. "Stan giving me this project is probably the best thing that could happen to me at that point."

By Kristen Coyne