The pursuits of science and art have a lot in common, as was amply in evidence one day last summer when sculptor Carolyn Henne visited the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory. For that afternoon, it became the National High Magnetic Field Museum.

While touring the lab’s unique instruments and facilities, the Florida State University art professor also viewed a kind of “found art” hidden in plain view. On whiteboards depicting the collaborative, creative work of science, Henne saw works of art. Studying them with an artist’s sensibility, she saw echoes of modern masters, including the layering of Nancy Spero, the cryptic markings of Cy Twombly and the symbolism of Elizabeth Murray.

The whiteboard is indeed the scientist’s canvas, a place to collaborate and create, to sketch diagrams, equations and graphs using the Fauvist reds, greens, blues and yellows available in his pack of markers.

Carolyn Henne

It doesn't matter, said Henne, that she might not know the intent behind those bold scribbles; that’s often the case in abstract expressionism and other modern and contemporary styles of art.

"But there's enough there to allow you to engage, because you know these things have information embedded in them," Henne said. "Now, whether or not I can pull that particular information out, probably that will never happen. But I can be interested in it in a more visual way."

Like many museum masterpieces, observed Henne, the whiteboards display the "mark making" artists use to work through issues and communicate that process to others.

"Mark making is all designed to move yourself closer to some sort of solved problem or answer to a question," Henne said. "Scientists do that and artists do that. … It can be done with a brush, it can be done sculpturally, it can be etched into metal, or (it can be) this kind of mark making, which is just reflecting and communicating thought and moving through an idea."

Scientists use other tools to record ideas: lab notebooks, image processing software and, of course, PowerPoint. Still, there is something unique about the scale, physicality and erasability of a whiteboard. It invites collaboration and expands thinking in ways pages and computer screens can't.

"It's faster and it's bigger and it's easier to be animated," noted National MagLab physicist William Coniglio, one of the artist-scientists Henne spoke with on her visit.

Here's a small sampling of the whiteboard collection currently housed at the MagLab museum. Share your own whiteboard artistry on social media @nationalmaglab.

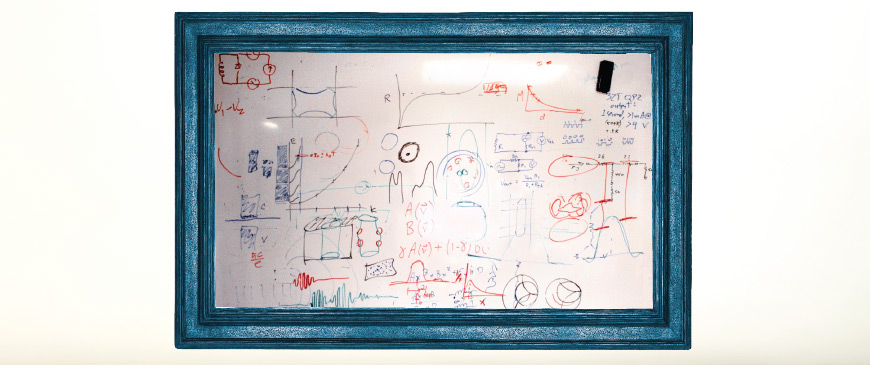

"Scratchpad"

Medium: Marker on Whiteboard

Artist-Scientist: William Coniglio

If the whiteboard in the office of William Coniglio could talk, it would be deafening.

"There are 20 discussions on this board," he said.

Coniglio reserves the white rectangle that fills one office wall for teaching. As to its composition, he said, conversations with tall students are on top, and those with shorter students are on the bottom. Overlapping reds and greens and blues, each color a new conversation, are like partygoers yelling to be heard above the din.

He has long since given up trying to erase the obstinate older markings.

"You just pick a complementary color and just go right over top of it," Coniglio said. And he dismissed the scribbles as science ephemera: The really good stuff ends up in his lab notebook, he said.

Pointing to a vase-like green and red shape, Henne asked if it represented an object being connected to another. In fact, Coniglio explained, it depicted a Fermi surface, an obtuse physics concept. But as with any work of art, Henne did not need to know such details in order to appreciate the work through her own filters.

"It's probably more interesting for me to come up with all my own explanations for what I'm seeing on here as opposed to you telling me what it really is," she told Coniglio. "And I think that's true when artists finish a work and it goes out in the world."

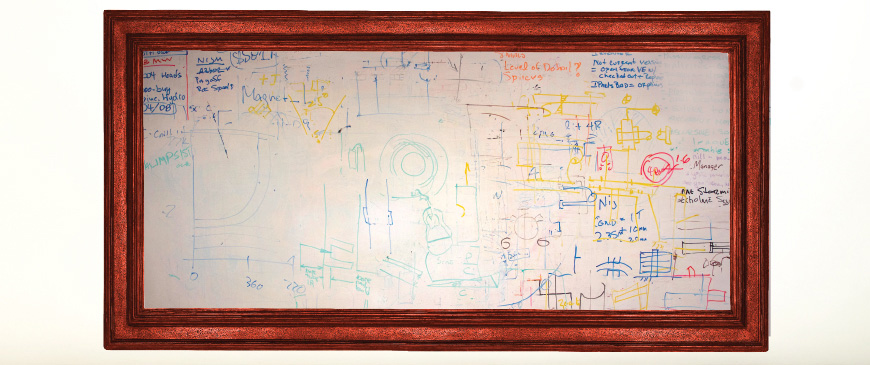

"Mayhem"

Medium: Marker on Whiteboard

Artist-Scientist: Scott Bole

The office of magnet engineer Scott Bole is home to many artsy artifacts, including fake bills dangling from ceiling tiles, a retired magnet part revamped into a lava lamp and, of course, an expansive whiteboard covered with ideas, to-do lists, graphs and magnet designs. To Henne, it brought to mind the term palimpsest, which refers to a reused writing surface that bears the traces of earlier markings. Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat was known to use his canvases like palimpsests. Whether purposefully or not, Bole does the same. Featuring the smudges of half-hearted erasures, his whiteboard, Henne noted, was like "a depiction of time."

"So there was removal, but there was still evidence of what had been there before," she said. "As a sculptor, I'm really attracted to that idea. But also, in a lot of drawings and paintings, there's evidence of what was there before."

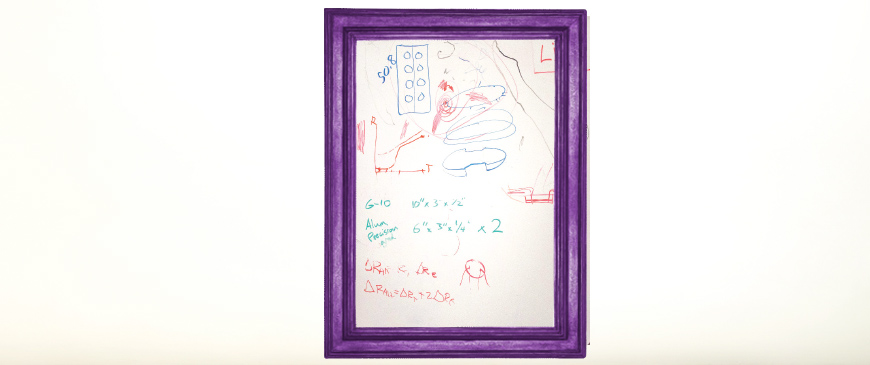

"Untitled"

Medium: Marker on Whiteboard

Artist-Scientist: Anonymous

Many of the lab's whiteboards are located in break rooms, hallways or other common spaces, so the artist-scientists behind them are impossible to know. That makes them all the more intriguing, as with this small whiteboard found in an uninhabited cubicle.

"If this was in a gallery, one of the things that I'd be most interested in is this activity that is happening right here," said Henne, pointing to a series of discs that look a bit like UFOs. "That somehow feels like it’s related to this graph, so I would be kind of working through that."

Given the board's anonymity, its mysterious markings seemed all the more poignant.

"This is a very strange thing," Henne continued, pointing to a red circle at the bottom of the board, which to her evoked a face with bleeding eyes.

Just to the left of that disturbing visage was a formula relating to superconductivity. Henne misread it, but in an interesting way — as "the change in fall," rather than the change in all of the electrical resistance (represented by "R"). With that poetic interpretation, it was if Henne had picked up a marker and added her own layer of meaning to the piece.

"There's a lot there for a viewer or a layperson to kind of investigate," she said.

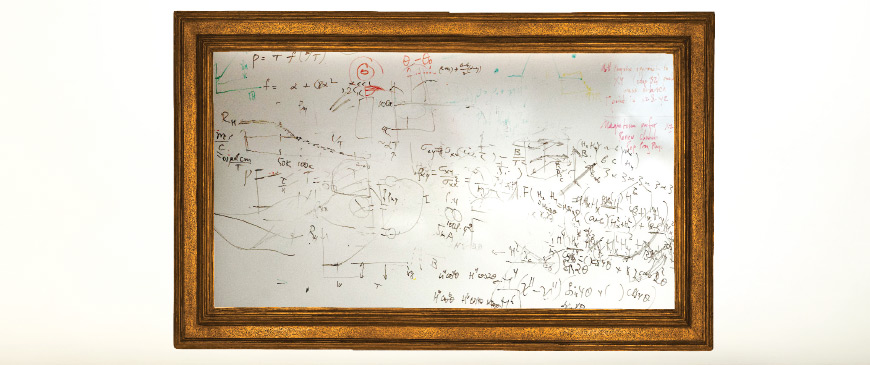

"Scientist at Work"

Medium: Marker on Whiteboard

Artist-Scientist: Arkady Shekhter

At this whiteboard, Henne's eyes were instantly drawn to the overlapping, monochromatic formulas scrawled in the lower right corner. On top of them, repeating diagonal lines looked to have been added by a vehement hand.

"Compositionally this is the focal area, because it's the busiest and most interesting in terms of worked surface," she said. There was a lot of energy in those markings, she noted, as if the scientist-artist was striving to make a point.

That artist then entered the room. With a quiet intensity, physicist Arkady Shekhter picked up a black marker and, adding to the ruckus of black swirls and angles, explained the science behind those markings. Although he quickly ascended to levels beyond the capacity of most laypeople to understand, his fervor, at least, was plain. As he sketched and talked, sketched and talked, Henne thought of Swiss artist Alberto Giacometti, known for working his drawings so energetically he would cut right through the paper.

"There's a compulsion to go over it — get it right, get it right — and I was seeing that in some of the things that he was doing," Henne later observed.

Shehter prefers old-school chalkboards to whiteboards. Either surface, however, plays a critical role in the scientific process. As a theorist, he spends a lot of time thinking. But eventually he has to present that thinking to others, and that’s where the board comes in.

"Sometimes you realize it’s complete nonsense; sometimes it makes you think about something else," Shekhter said. "It's very important just to verbalize it, and to verbalize it in front of other people."

Making the contents of his brain manifest with whiteboard designs, plots and formulas brings them to life. And after all, Shekhter said, "Physics is a story."

View more whiteboard art below.