Contact: Kristin Roberts

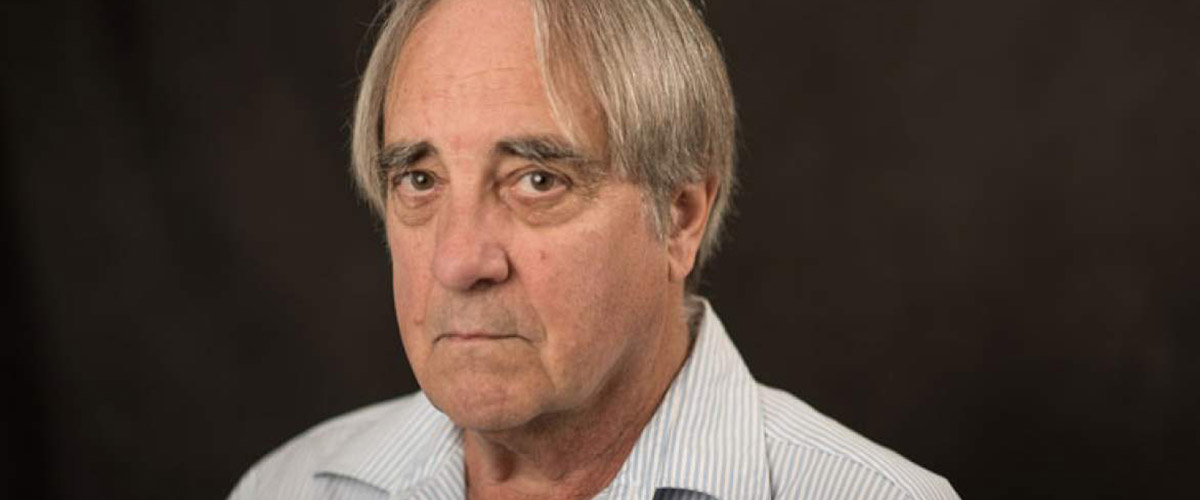

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Dr. James Brooks, director of the MagLab's Condensed Matter Science Experimental Program, chair of the Florida State University Physics Department, and a much-beloved teacher, mentor and friend, passed away last week.

"This is a great tragedy for us all personally and for the MagLab as an institution," said MagLab Director Gregory Boebinger, who first met Brooks in 1982.

ture and high magnetic field physics for decades. A fellow of the American Physical Society, he pioneered the use of dilution refrigerators in high-field resistive magnets and held the record for doing an experiment in the largest steady state magnetic field (47.8 tesla). He was devoted to educational outreach and to cast-netting for mullet near his Gulf Coast home.

Brooks worked in experimental low temperature and high magnetic field physics for decades. A fellow of the American Physical Society, he pioneered the use of dilution refrigerators in high-field resistive magnets and held the record for doing an experiment in the largest steady state magnetic field (47.8 tesla). He was devoted to educational outreach and to cast-netting for mullet near his Gulf Coast home.

Brooks's remarkable and productive career is summarized in his lengthy list of publications and other achievements. But a picture of this jovial, giving and passionate scientist is perhaps best drawn by the memories of the many people at the lab whose lives he graced.

How to make a mentor

Like any good physicist, Jim Brooks knew a lot of equations. Modern physics, after all, is built on scores of them, such as F = m*a (Newton's second law of motion) and E=mc2 (energy equals mass multiplied by the speed of light squared — thanks, Einstein!).

So it's not entirely kooky to think of Brooks himself as an equation. Given his offbeat sense of humor (he did, after all, pluck a frog from a pond and levitate it in a magnet back when such stunts raised more chuckles than eyebrows), the idea might have tickled his funny bone.

Brooks passed away last year at age 70 after a 20-year career at the MagLab. A fellow of the American Physical Society, he worked in many areas of experimental, low-temperature and high magnetic field physics. As demanding as that research was, Brooks also devoted countless hours to mentoring students, post-docs and colleagues. By all accounts, he was as passionate and gifted at that job as he was at physics: Every moment was a teachable moment for Brooks.

"Jim had an unusually broad range of research interests, and he was also an exceptional human being," said MagLab Director Greg Boebinger, whose friendship with Brooks spanned three decades. "He took great pride in applying his expertise to help younger researchers advance in their careers, which has made his impact on physics all the greater."

Brooks' sudden death prompted a flood of remembrances that spoke as much to his legacy as a mentor as to his impact as a scientist. Below, we've distilled the stories of Brooks the Mentor — or Brooks-sensei, as he was fondly known among his Japanese students and colleagues — into a kind of equation. Add up all these traits and you're bound to come out with a fine mentor on the other side of the equal sign. While no one could ever fill his Birkenstocks, his example may inspire others to walk that same path, helping advance science through quality mentoring for a long time to come.

A champion for others

Those who knew Brooks best describe a man whose passion for science was unfettered by ego. "He never pretended to know what he didn't know," said Andhika Kiswandhi, a former Brooks post-doc now at the University of Texas at Dallas, "and he loved to learn from everyone, including his own students." When he advised on a successful project or paper, he scrupulously side-stepped the spotlight.

"He always cared about our careers," said MagLab researcher Eden Steven, another of the half-dozen grad students and postdocs Brooks was supervising at the time of his death. "On every occasion when there was an opportunity for us to shine, he would always give us that chance."

Brooks groomed his students for independence and success. He taught them how to focus their work, when to stop taking data and how to write well. Some mentors, said Steven, will write a paper based on a student's work in order to get the research published more quickly. Not Brooks: He pushed students to author their own papers and to take the credit — even though it meant reviewing every draft along the way.

Brooks didn't reserve encouragement for his students only. When physicist David Graf sought advice as a newbie to the lab in the late 1990s, the common refrain was, "Go see Brooks."

"It didn't matter if you were his student or post-doc: His door was open," said Graf. "He would guide any willing student through the scientific process and then push them forward to take the credit for any success."

The many young scientists who sought out Brooks' office — a space blanketed by papers, instruments, travel mementos and thank-you gifts — always found the door ajar. Brooks also opened many figurative doors for them through introductions and recommendation letters that could clinch a new job or award. When physicist Irinel Chiorescu first came to the MagLab and Florida State University, Brooks took him under his wing. After winning a prestigious National Science Foundation award for early-career scientists, Chiorescu placed a late-night call to Brooks so that he was the first to know.

"I remember he was quite thrilled about it," said Chiorescu. "He was as happy as I was."

Space for mistakes

Of Brooks' many philosophies about science, this was surely one: You can't do it right without making a mess and a few mistakes along the way.

The younger the scientist, of course, the more frequent the mistakes. As a mentor, Brooks knew his students would sometimes stumble, and he always made room for that critical part of the scientific process.

"He didn't watch your back all the time: He gave you an idea and let you work on your own schedule," said Steven. "He always told us that creativity is something you cannot predict. It doesn't work this way. You need to give them space."

Brooks' love for teaching even extended to school-age kids. He taught impromptu physics lessons to pint-size friends using homemade tin-foil masks and magnets; dented classroom ceilings with projectiles in the name of science; and at the annual MagLab Open House entertained thousands of kids and kids-at-heart with demonstrations involving loud noises and smashed fruit. Brooks was never one to spoon-feed science: He threw down the ingredients like a gauntlet and then made room for sticky, smelly, blooper-filled science to happen.

Educational consultant Brenda Crouch, who worked many years with Brooks teaching kids and educators hands-on science through the Panhandle Area Educational Consortium, was awed by his ability to point students in the right direction, then step back and make way for learning. "After he explained how something worked, he really didn't give the students a lot of details, except to say, 'This is what it does; this is how it works. Let's see what you can do.'"

Work hard…

With his Hawaiian shirts, mop of gray hair and socks-and-sandals footwear, Brooks looked the part of a chill dude. That hippieesque demeanor notwithstanding, few people worked harder.

"Nothing was asking too much. He just worked very, very hard," said Crouch. And he never shirked the grunt work. "He was not an assigner of tasks," she added. "He was, 'Let's roll up our sleeves and get the work done.'"

That dedication inspired a similar work ethic in his students. "He never asked us to come in during the weekend, but we always came," said Steven. "I think what drives us is that we saw him work so hard for us, and that made us in turn want to repay that favor."

…Play hard

Long hours in the lab and at the computer could well make for a bunch of dull (and ornery) scientists. Luckily, Brooks had a fun side. He was famous for the parties he hosted, attended or spontaneously sparked: Even a meeting could be a party, as physicist Graf discovered when he first met Brooks back in 1999.

"He was laughing, drinking beer, looking at data and having a great time discussing the results," recalled Graf. "It was the first time of many that he would show me that you could work and have fun at the same time."

In Brooks' book, science was best done with a smile … the more devilish, the better.

Brooks taught MagLab Director Boebinger this lesson early in his career. An assistant professor at Boston University at the time, Brooks shared a magnet with then-grad student Boebinger. One day, Brooks and a visiting scientist were using it for a sensitive experiment on the fractional quantum Hall effect. Tinkering with equipment on his side of the lab, Boebinger chose an ill-fated moment to power up a drill, causing electrical spikes on their data and wrecking the day's work.

The irate scientist fumed. An abashed Boebinger wanted to crawl under a dilution refrigerator.

Brooks? He cracked up.

"It was Brooks who saw the humor and turned things into a teaching moment," said Boebinger.

Humor was indeed one of Brooks' favorite teaching tools, and he wielded it often to tear down walls that inhibited learning.

"He was just irreverent enough to really appeal to his students," said Crouch. "He had a great relationship with the students. He was so accessible to them."

An avid angler who spent rare downtime fishing at his beachfront home, Brooks had enough kid in him to know how to hook a future scientist. Dropping watermelons from the roof of FSU's seven-story physics building ("There was a controlled experiment," recalled MagLab physicist Eun Sang Choi, "but most of the time it was just fun to watch."); smashing objects with junkyard magnets; building "mouse mobiles" to teach energy and friction; incorporating liquid nitrogen into demos whenever feasible: These were just some of Brooks' science stunts. So of course, when he and Crouch decided to use the unique, liquid/solid substance called "oobleck" to teach a group of educators about non-Newtonian fluids, a simple beaker of the stuff wouldn't do. They needed a whole swimming pool full so that they could try to scamper across it before solid turned to liquid, sending them sinking into the goo.

"And you can guess who led the pack," said Crouch.

Know your audience

Although Brooks deployed fun to maximum pedagogical benefit, he was not a one-size-fits-all mentor. Thanks to a keen emotional intelligence, he could discern people's needs, fears and strengths quite well.

"He taught every student differently," said Steven. "He really knew which buttons to push."

Whether you were a kid or adult, physicist or layperson, teacher or student, he knew how to connect, Crouch said. "He had such a gift … for figuring out ways to make complex science content understandable."

Former student Arjun Narayanan said he still turns to his old professor when stumped by something: "Often … I have found the concept I have been struggling with best explained in some paragraph of an old paper of his."

For MagLab physicist Chiorescu, Brooks' secret to science communication was being a caring listener. Whenever he came to Brooks with an issue, the senior scientist listened carefully, interrupting with a question only as needed.

"He was not a talker who spends minutes and minutes talking. He was precise, and all the words had a lot of weight," said Chiorescu. "I had the feeling that he was listening to everybody and always taking that to his heart and trying to help everybody."

In a word: Be a mensch

Of all the attributes that made Brooks a fine mentor, the one remembered most fondly may also be the one most difficult to duplicate: Kindness. He offered to help people move, loaned them his truck, fetched them from the airport with a favorite beverage at the ready. His memorial page chronicles thoughtful acts, large and small.

"Jim was a very caring person, and he had a very open heart for everybody who needed his help and support," wrote physicist Hans Schneider-Muntau.

"I hope someday to learn to treat others with grace, humility, and unearned affection from the first moment, as he did with me," noted his one-time student Narayanan.

The laboratory where Brooks' group worked was, like his office, cluttered with the tools and byproducts of science. Walking in, you felt like you've interrupted a dozen different experiments. Working there recently, the young scientists were excited to observe an interesting phenomenon. The thrill of discovery was quickly dampened, however, by the realization that their mentor was no longer there to share it with them.

"We can talk about it to someone," said Steven, "but nobody will appreciate it as much as Brooks."

Colleagues and Students Remember

"I've known Brooks since 1982 when I was a grad student and he was an Assistant Professor at Boston University. We shared the same lab, sliding the magnet back and forth on rails depending on who had magnet time during any given week. Circumstances and personalities cast us as both friends, but also occasional competitors, because he was assigned to host Emilio Mendez, head of the IBM group working on the fractional quantum Hall effect. I was in the Stormer/Tsui (i.e. Bell Labs/Princeton) group. During one of their magnet runs, I was making alterations on our dilution refrigerator. As soon as I powered up the drill, electrical spikes showed up on their data, ruining the mobility of the delicate two-dimensional electron system in their sample for the rest of the day (until they could thermally cycle the sample back to room temperature). Emilio was upset. I felt terrible. It was Brooks who saw the humor and turned things into a teaching moment."

— Greg Boebinger

"Dr. Brooks was the best and the most dedicated mentor I have had. He worked very hard, including the weekends, to make sure we will be successful. He always made sure we had the best environment to excel and be creative. He took us in when we couldn't even use an ohmmeter yet. And his mentorship has made us better than we can ever be all because of him. A lot of us are not the brightest and the most talented, but he can truly see our passion and help us achieve our dreams. His group is always very diverse, yet with his outgoing personality and kindness in his own way, he managed to get his group to be cohesive and have great teamwork. … No words will be enough to describe his positive impacts to people around him. We all will miss him greatly and I regret not having a chance to say thank you to him one more time."

— Eden Stevens

"A fourth century Archbishop of Constantinople, St. John Chrysostum said, 'He who we loved is no longer where he was, he is where we are.'

"A life is ultimately measurable in how many people show up at the funeral and what they say about the dear absent. Jim lived well. He will be missed."

— Pradeep Kumar

"He was my 'FSU mentor' during my tenure-track years and he was a true mentor, always coming with great advice regarding all sorts of things, research or teaching related. He had quite often an unconventional approach about research methods. You would often wonder how could someone come up with such an idea to deal with quite a complex phenomenon. As a group and department leader, he was dedicated to meaningful changes and he was a very hard-working person. And he was able to do all that while keeping things in a happy perspective, often contagious."

— Irinel Chiorescu

"In the eight years that I've been at the MagLab, a happy moment of any day occurred when I either ran into Jim coming into the lab or, as often happened, we shared email exchanges. Often it was — what wonderful exotic place are you at the moment and are you having fun? In fact fun is what I associate with Jim Brooks. He was a humanist. He made life better."

— David Larbalestier

"I still remember the moment I first met with James in the lobby at the MagLab after I moved to FSU in the summer of 2012. He is the first one who welcomed me and walked me around at the MagLab. James is the kind of person that even a quiet person like me would love to make friends with. In the past two years, I received numerous supports from him on teaching, research, grant writing, etc. He never turned me down."

— Wei Guo

"Everyone in Tallahassee will be aware of the huge impact he has had at FSU. But what many of you may not realize is that he has been just as active in the international scientific community, constantly traveling to Asia, growing scientific networks, and mentoring tons of young people from all around the world. … Brooks was also the reason I moved to Tallahassee in 1995, where I soon met my wife (he and Janet attended our wedding), and where we now live happily with four wonderful children. Brooks touched our lives in so many special ways. We will truly miss him.

— Stephen Hill

"Brooks was an enthusiast. He loved the science, the magnets, the quantum oscillations, the Fermi surfaces, but most of all, he loved the young people that he educated, the people whose love for science he helped grow and bloom. Brooks always worked with many people — he was surrounded by students, colleagues, users, visitors. He thrived building this community. I remember him taking his group, every Friday, late in the afternoon, to the golf course cafeteria, for a group meeting over a pitcher of beer and much discussion and many jokes. And it is those jokes - his humor - that will probably reman best remembered by many of us. He often saw the funny side of things, and this helped many of us in times which were not always easy, it helped people see the good side, not only the hard reality of life."

— Vlad Dobrosavljevic

"He was a great teacher. He made even the most complex phenomena look simple and understandable. It was one of the only classes I used to look forward to, especially to his homework's. During the entire course not only did he introduce us to different kinds of research inside and outside MagLab, he also inspired us to become great scientists … I wish I could have thanked him one last time for making me believe in myself, for giving me several valuable opportunities to grow as a young researcher and motivating me."

— Lakshmi Bhaskaran

"…[Brooks] sometimes would work together with us [graduate students] during some important magnet time and stayed up until 2:30 a.m., as well. Moreover, after the students worked a long shift until midnight, he would ask if there was anything that he could do to help in the morning, be it running the magnet or cleaning up the cell. This is clearly an ultimate form of teamwork and equality, that he sees us not only as students, but also as partners, as part of a team, as equals, that we're in this together. … Sometimes I disagreed with his views. Of course my views turned out to be wrong, but he gave them some thought, anyway, before he told me why and how they were incorrect. This is also what made him a great scientist and mentor."

— Andhika Kiswandhi